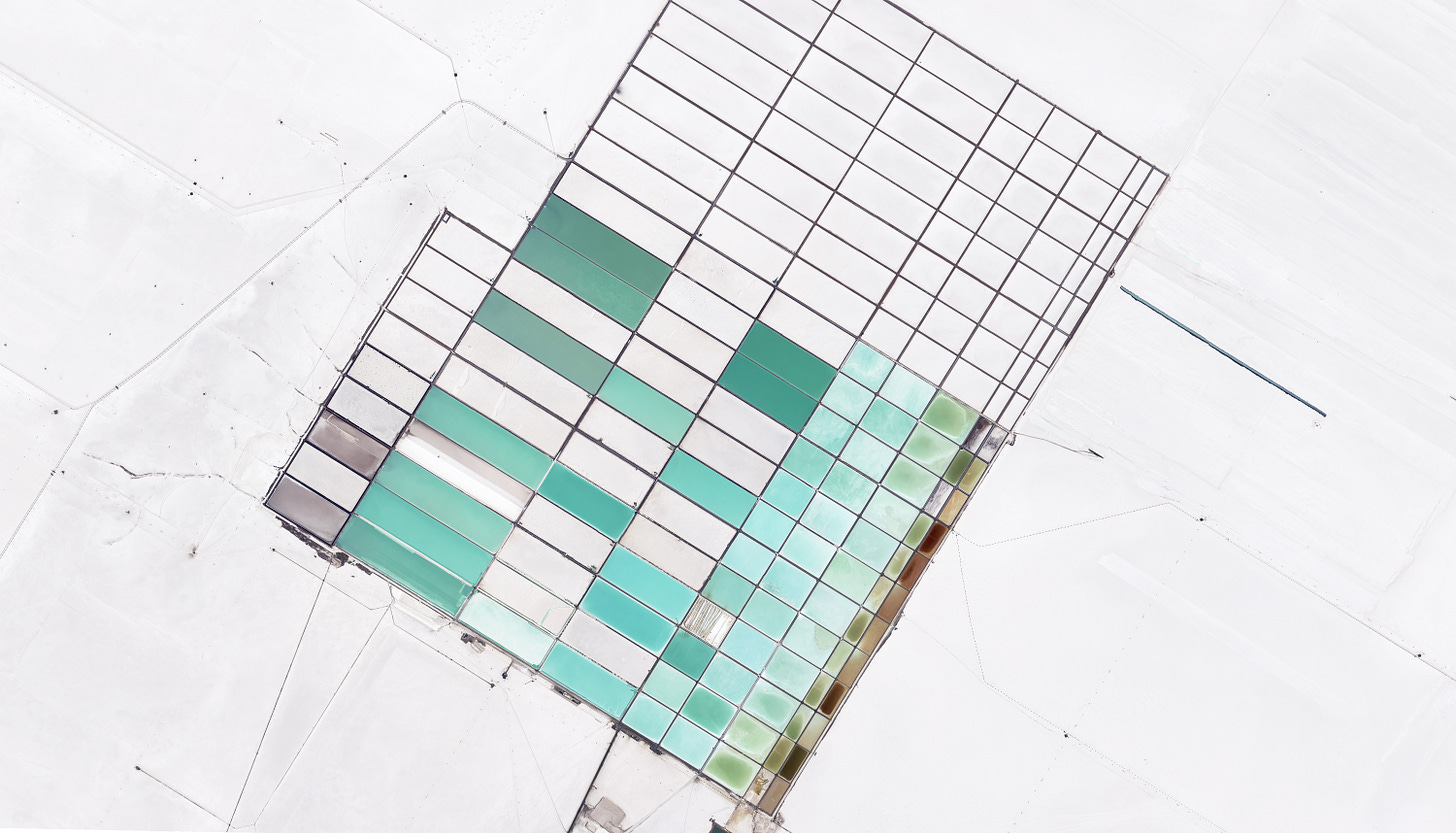

Lithium Mirage

Cerulean pools shimmering in the hothouse heat, building a vision for the distant future, and whether a California sacrifice zone can be transformed.

“I worried about the shortsightedness of an environmental ethos only focused on carbon emissions. One that tells people to be better consumers without also instilling a fierce love of biodiversity.” — Ben Crair, “The Island Where Environmentalism Implodes”

“These places look inhuman, for their scale and for their poisons and hazards, but they’re the landscapes on which most human beings now depend.” — Rebecca Solnit, “Creative Destruction”

There’s just something about someone holding a gun that compels me to take what they’re saying seriously. They might be asking why I’m on this particular stretch of Nevada desert, or if that loud drone pestering golfers is mine. The answers don’t really matter. I just find myself nodding along in agreement, eyes fastened on the sidepiece.

When I eventually must explain to this particular man why I’m on private property, I respond that I had no idea. Of course, I had some idea; a lot of people ask me how I make my images and the answer is that I trespass—or usually my drone does. In the end, I’m not sure if he was police, private security, or an uppity caddie, but he seemed adamant about my leaving.

What a shame. If he had asked me to stay and chat awhile, then maybe he could have joined me in trying to answer a burning question of mine: is there such a thing as sustainable resource extraction?

It is August 2023, there is a heat wave, and I am taking images of water-intensive golf courses and lithium mines. I am mostly interested in the latter, for the lithium pools slowly evaporating in the Nevada desert are a glimpse into our weird energy future. They are the beginnings of what might be called a post-extractivism frontier. Does that sound too academic? Allow me to try again.

The standard image of an ecotopia is a green field with slowly rotating wind turbines, rooftop solar with pollinator-friendly front yards, and electric vehicles that make cute little sci-fi noises. These ideal visions are surely part of the picture, but they conceal the reality that enables them. Travel to the bottom of their supply chains and you’ll find the substrate: the bituminous coal mines that produce steel turbine blades and the heavy element mines that power batteries.

Thus, the future will not be solarpunk; the green utopian vision we’re building today is still entangled with extractivism. It will be pock-marked and cratered with those hallmarks of industry: mines, smokestacks, refineries, and transmission lines. But if there is a sign that the times are changing, that a new approach to resource extraction is possible, it just might exist among the sky blue pools of lithium evaporating in the desert.

Lithium’s story begins with the Big Bang, making it both old and important. The primordial metal then spent a few billion years doing god knows what until we Homo sapiens, critters of stardust too, discovered its medicinal benefits as a sort of psychiatric panacea. Its early promise to cure all ailments proved mostly incorrect, but its potential to store energy in electric batteries sparked a new mania.

Any TSA agent can tell you how important lithium is to the modern economy; in fact they do every time they tell you to put your lithium-ion devices in your carry-on. In a few short decades, this prehistoric metal has dominated the rechargeable battery market. Its end products are now found everywhere, but its raw deposits are unevenly distributed. Reserves are mostly found in places like Chile, Australia, Argentina, and Bolivia. It is also found in the United States, though the Silver Peak Mine is currently the only active one. Thus securing lithium supply lines has become the material focus of the race to electrify everything. And it is a race the US is sorely losing.

And that’s literally all I’m going to talk about the markets of lithium and critical mineral extraction in general. For more, check out the NYT’s “The Lithium Gold Rush”, Cobalt Red by Siddharth Kara, and Material World by Ed Conway.

In lieu of all that, I’d rather spend these meager paragraphs discussing the problem of long-term vision, environmental infighting, sacrifice zones, and a paradox of the moment: lithium won’t solve the climate crisis alone, but without it there’s likely no hope.

Algae blooms are darkening the color of the ocean. Air pollution is obscuring views of the Himalayas. The consequences of unfettered carbon emissions were already difficult to visualize—scattered in time and place as they are—but they are now clouding our very very ability to see.

Good photography and reporting helps cut through this haze. But there is a new uncanny challenge: solutions to the climate crisis are now more difficult to communicate than its catastrophic impacts. This might be better called a crisis of vision: what we collectively imagine a civilization cured of its fossil fuel addiction to look like at a high-level.

Part of this is due to the competing interests of different environmental groups. Let’s generalize the infighting for a moment. Group 1 wants to decarbonize transportation through EVs. So Company A builds EVs for Group 1. Company B builds a lithium mine to supply Company A. Group 2 sues Company B because it threatens an endangered species of buckwheat. Group 1 begins to question the moral character of Company A’s founder and wonders whether EVs and, while we’re at it, recycling are really making a difference at all. Companies C through Z then come along and build AI programs to compound the energy demand responsible for this whole predicament in the first place. And the whole time most of us are simply asking for more fucking trains.

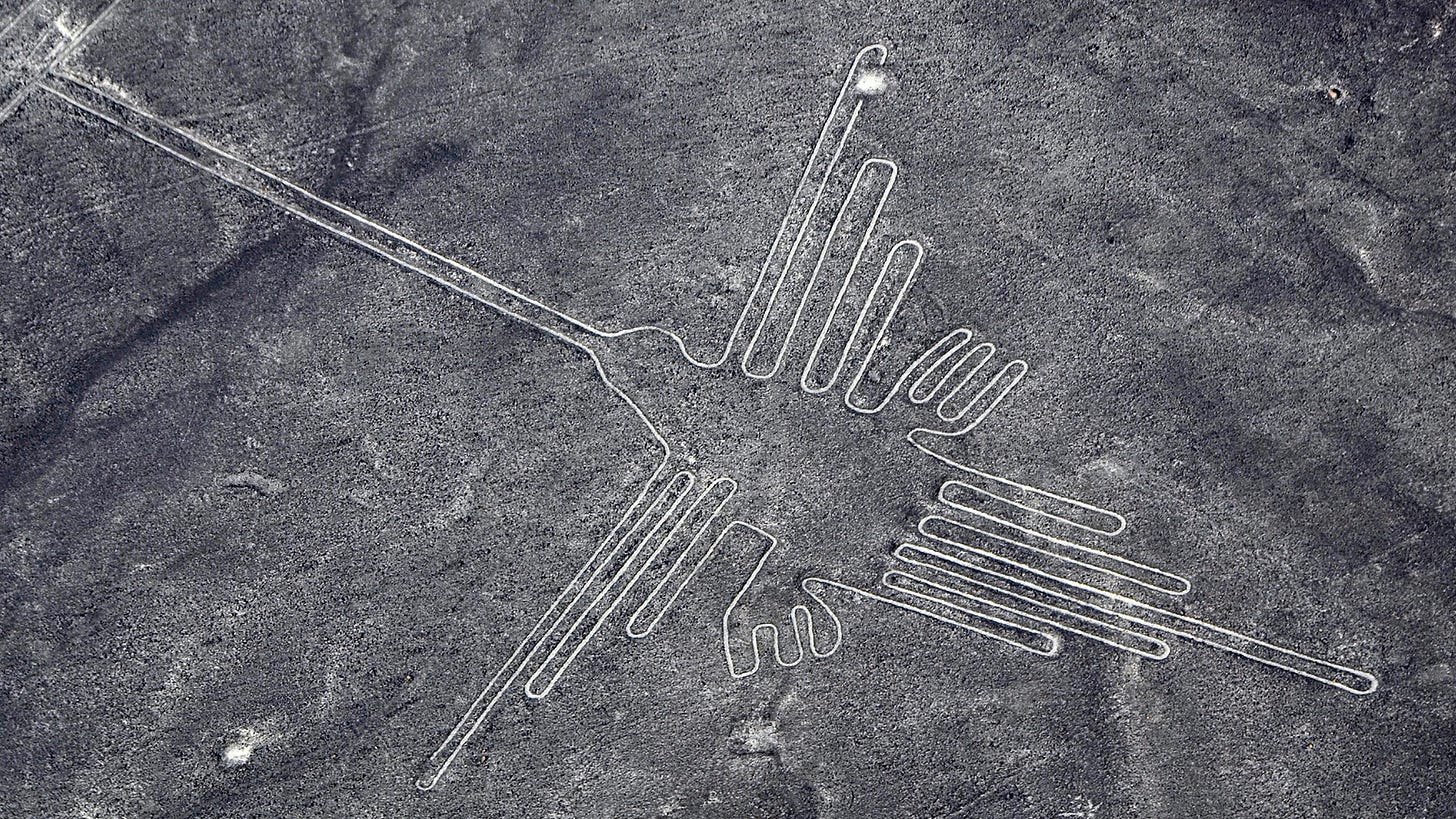

I question how we keep on track when one environmental group’s solution is another’s apocalypse. And when I find myself asking that question, I think of evolution, geoglyphs, and cathedrals—as pretentious as that sounds.

I think of evolution because it is a design process with no end goal. It simply iterates to solve immediate environmental challenges. Do that long enough and harmonious structures of infinite complexity emerge.

I think of geoglyphs—in particular the ancient ones found in what is now Peru—because they were made without an ability to perceive them on the whole. The Nazca people carved hundreds of feet, sometimes miles, of material out of the landscape to create a sprawling series of biomorphs. Their creators could trace its outlines or catch an acute glimpse from a nearby hill. but it wasn’t until the advent of the plane, and then later the satellite, that an aerial view would be capable of beholding them in their entirety.

And I think of the stonemasons of Medieval Europe who took centuries to build the Gothic cathedrals still standing today. These were, like the Nazca Lines, made according to a plan. But where the Nazca people couldn’t see physically, the stonemasons couldn’t see in time. A generation of workers might only lay marble without ever witnessing its spires rise skyward.

Three generative processes that transform the material stuff of the world into constructions for posterity. There was no master architect perched above, shouting down instruction to the craftsmen. And yet they were built anyway.

The question is now whether we can do that with our energy system.

Stand on the shore of California’s Salton Sea and squint your eyes. Peer out beyond the oppressive sun, through the clouds of carcinogenic dust, over the blooming algae, and you might catch sight of a dream. Whether it is dead or dying will be determined in the following years.

Near the Mexican border, tucked between San Diego and Joshua Tree, is the Inland Empire’s inland sea. The Salton Sea is an ancient basin, but the water there today was collected in 1905 after an irrigation canal broke. As the waters rose, capitalists sniffed an opportunity and flocked to its shores, much like the millions of birds who were now adding a new stop on their migration. Throughout the 1950s and 60s, tourism was so explosive that it surpassed the number of annual visitors to Yosemite.

But the area never quite shed its agricultural persona. And the nitrogen runoff from fertilizers seeped into the Salton Sea. With nowhere to go, it stayed put, adding algae to the briny mix. Unsurprisingly, tourism soon crashed; sunbathers found it hard to lay down a towel on a beach covered with the skeletons of dead fish. And thus the vision of a ‘Southern California Tahoe’ imploded.

Walk along the Salton Sea’s shores today and a smattering of neighborhoods sit among the relics of that hope-filled era. Experimental communities like Bombay Beach and Salvation Mountain speak to its marginal standing. But it is the alarming rate of asthma among the area’s children (20-22%, 3x the national rate) that is most damning.

The Salton Sea is a sacrifice zone: places where the health of local populations are sacrificed for the economic prosperity of others. They are the coal mines in West Virginia and the petroleum refineries in Mississippi, also known as Cancer Alley. Sacrifice zones are penned by similar historical, political, socioeconomic, and racist lines. But unlike the Salton Sea, most zones didn’t just find $540 billion worth of lithium reserves beneath them.

The solarpunk vision for what happens next in the Salton Sea involves flipping the sacrifice zone model on its head. It is to create a system that improves the welfare of the local population while also providing materials the world needs. It accounts for the millions of migratory birds, the farmers sharing resources with the mining, and, reluctantly, the shareholders of the lithium companies.

There is a short window to get it right. Otherwise the Salton Sea’s lithium development will simply mirror the state’s gold rush history: a few obtain a fortune, most remain impoverished, and a handful receive a pickaxe to the back of the head. A vision is as much defined by what’s included as what’s left out. And for now the vision set forth by critical minerals like lithium leaves out plenty.

To place our full faith in lithium is to cement the extractive and pollutive systems already in place. It is a fantasy that pretends lithium is a panacea instead of an excuse to make minimal changes to the capitalist approach that got us into this mess in the first place. We can buy an EV or stick with the gas guzzler, we can exit right or burn on straight ahead, but we are driving on roads we did not build.

The gun has lingered in memory primarily because I can’t help but admire how effective it functions as a communication device. The contraption requires no description. It compels you to look at it, as if it holds its own visual gravity. But more importantly, the message it sends is unequivocable.

I had once thought that images of environmental ruin might serve as a similar device, an effective shorthand to trigger a common emotion. But images of the new extraction frontier challenge this idea. The industrial sites of extraction appear jaundiced, not bloodshot. The message is muddy. Contamination is tempered by symbols of progress. At their best, these photographs illuminate the perils of supply lines and compel buyers to hold institutions accountable. Yet so often they fall short, leaving their viewer to ‘bear witness’ and ‘start conversations.’

I am rapidly losing faith in this type of imagery’s capacity to influence, the currency of which is either anger or temporary inspiration. And I didn’t feel either of those as I stared out across the pools of lithium, shimmering under the August sun like a cerulean mirror or a puddle of Dr. Manhattan’s piss.

No, what I found staring back in that lithium reflection was an uncanny despair that the vision of so many environmentalists, myself included, are placed in pools of brine, waiting to crystallize in the greenhouse heat.

If you squint your eyes in that desert sun, the line between miracle and mirage is thin. The vision should materialize if you just keep looking long enough. Wait there a while. Find a new height to perceive it. Ignore the briny sweat seeping into your eyes, and don’t anger the man with the rifle telling you to move along.

Written and photographed (unless otherwise indicated) by Ryder Kimball

Excellent essay