Digital Replicas

Tuvalu in the metaverse, digital twins, glitchy clouds, rainforests X-rayed, dire wolves resurrected, Voyager-1 among the cosmos, and a simulated Earth.

“What was vanishing as ecology was reappearing as imagery.” - Rebecca Solnit, River of Shadows

Politicians don’t usually make videos of incomprehensible horror. And yet one of the most unnerving clips on the Internet is a political speech by Simon Kofe, the minister for the large ocean state of Tuvalu. What begins with “warm Pacific greetings” from the tailored politician ends in a liminal place somewhere between Black Mirror and The Twilight Zone.

The soundtrack has the hollow and harrowing tone of impending doom as his sentences build to something resembling a righteous threat: “since COP26, the world has not acted, and so we in the Pacific have had to act.” Then, amid glitching pixels and distorted visuals, he states, “as our lands disappear, we have no choice but to become the world’s first digital nation.” The camera pulls away from the standard podium-and-flag close-up to reveal a small island with white sand and a black sky looming above. He is not speaking from Tuvalu, but from the cloud.

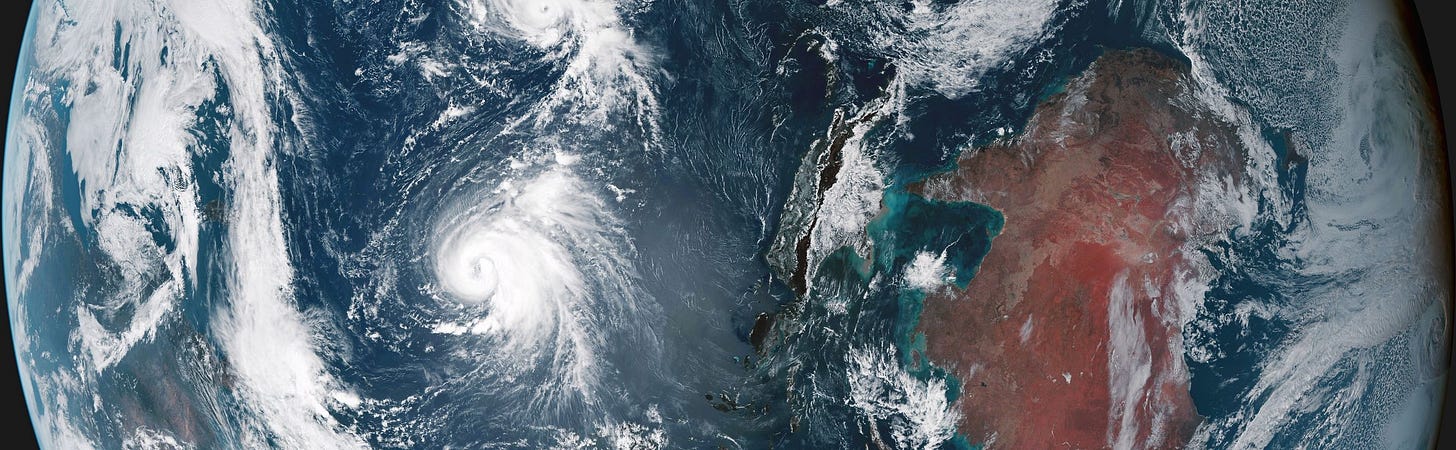

Scientists predict that rising sea levels will consume 95% of Tuvalu by 2100. The country, situated about halfway between Hawaii and Australia, has contributed less than 0.003% to global greenhouse gas emissions. That places like Tuvalu are positioned in the vanguard of severe climate impacts is tragically unethical. That their only recourse in the face of annihilation is the digitization of reality is uncanny.

Tuvalu’s “Future Now Project” entails uploading the country’s islands, structures, and physical beauty to the metaverse. Its purpose has a very practical aim in the preservation of the nation’s maritime boundaries and sovereignty—the first of what will surely become a growing number of legal actions as global warming alters borders and threatens statehood. But Tuvalu’s project has an emotional dimension too. It is a radical act of cultural preservation, a message in a bottle cast into the hungry tide, a seed launched into the digital cloud where there is no wind.

Enter the Digital Dungeon

Tuvalu’s entrance into the Matrix is but one of a growing number of digital replicas that, in one way or another, respond to the existential crisis of climate catastrophe and global unrest. But what Tuvalu is creating by necessity, many are entering voluntarily. As global warming renders swaths of the globe in “un-s” (uncomfortable, unraveling, unsafe, uninhabitable), the shimmering online mirror gains appeal.

You don’t need a magical wardrobe to enter these fairytale worlds, just a cellphone. In fact, these dully glowing portals are helping create virtual worlds too. The countless number of images and data points uploaded each day is transforming the material stuff of the Earth into the immaterial cloud, pixel by pixel. It is only happening slowly because there is so much of it.

This great open-source project has unfolded mostly innocently. For decades the Internet acted as a global repository for data; each uploaded text and image sent to this nascent planet like comets containing the raw materials for life. In the digital space, the infinite can be compressed. Structures rapidly emerged and the blueprint for civilization became accessible for (almost) all: Wikipedia—the great Library of Babel; social media—the human network; and Google Earth—the endless atlas.

There’s been no shortage of discussions pointing out this digital retreat. Each new generation enters a world ecologically diminished but technologically abundant. Escapism is so far-reaching that not even our poultry is safe. A new study found that chickens raised among projected virtual reality free-range environments were healthier than those without. The advances are developing so fast there’s no time to fly the coop.

Digital Twins

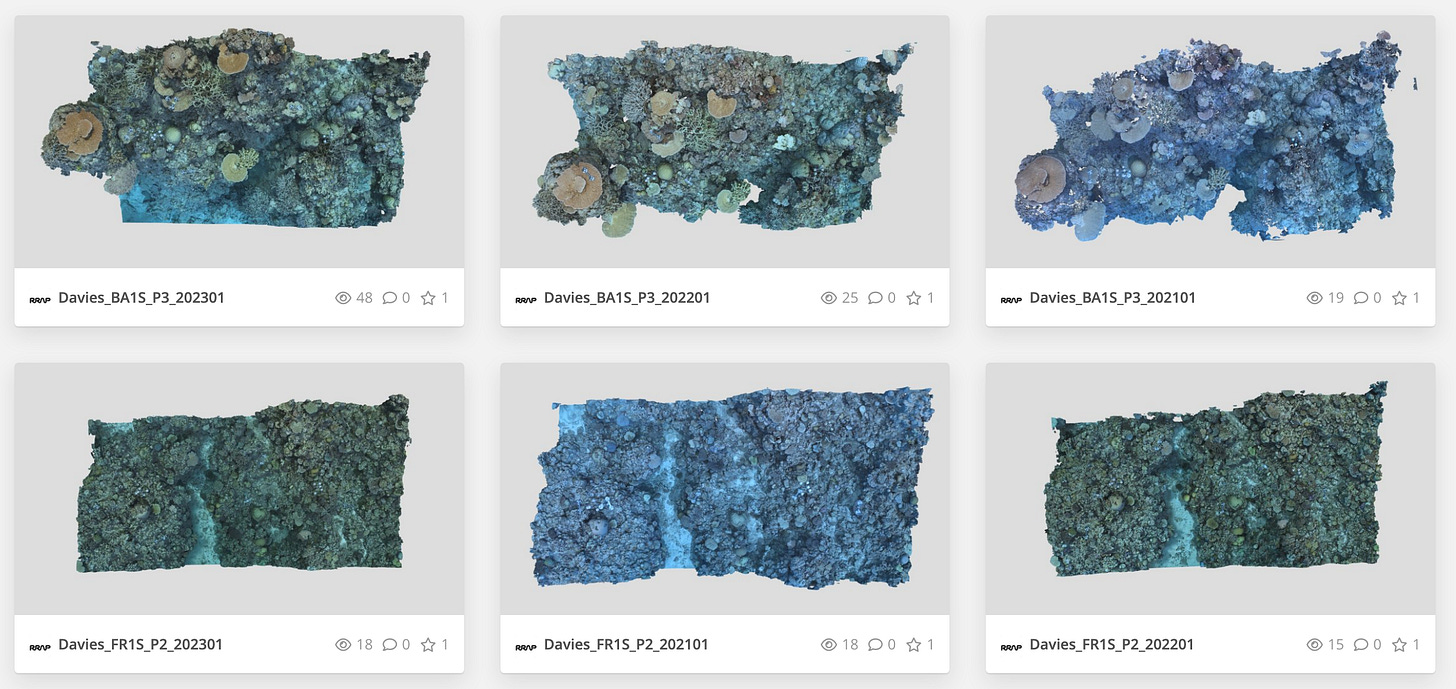

These digital replicas are so convincing because new technologies have revolutionized how objects are represented in virtual spaces. Point clouds model objects by plotting their surface with numerous “dots” in 3D space. Sensors like LiDAR can then scale this ability to create digital representations of entire cities or the Amazon rainforest. Pair this with cutting-edge video game engines and anyone with a controller can manipulate whole ecosystems.

But the same technologies that help chickens and Homo sapiens temporarily escape our confines have found another purpose. Enabled by recent advances in AI and computing power, Earth’s virtual domain no longer acts as a warehouse for data, but a playground for simulations. Companies have taken the two-dimensional copy and turned it into a three-dimensional model, like building a breathing being from a string of DNA polymers.

At its most basic level, a digital twin is a virtual representation of reality. It is an online model of something—a house, a wind turbine, Tokyo—that can be poked, prodded, altered, and studied. It is not a static snapshot. It is dynamic, alive (in a sense), and able to map the interactions between subject and influence. Simulations in the contained, digital world then provide insights about the physical outside.

Take Singapore, which recently finished firing lasers at itself to create Virtual Singapore. It is a detailed digital twin, modeled in 3D, and fed by real-time data. The government uses it to run simulations to triage climatic threats like heat urban island effect or find the areas most vulnerable to sea level rise. The engineered solutions based on these models are more effective and by extension save more lives—all for the cost of colossal computing power. Energy use aside, it’s already paying dividends, but it’s really just practice for the real challenge: a digital twin for the Earth itself.

Simulation Manipulation

To model the Earth is to gain unprecedented power—a literal orb to peer into and run simulations of various scenarios, say, the impact of a policy to reduce carbon emissions or what might happen if we nuked a hurricane. Like Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, this virtual Earth could be abused with all our hedonistic fantasy so that real Earth can remain relatively healthy. In the near future, this engine of prediction will undoubtedly save time, resources, and lives. Already AI is synthesizing multiple datasets to generate images of storm damage before it happens, helping to convince those in its way to move to safety.

Studies like these are already blurring the line between model and reality. Exponential advances in computing power and game engines only further place us closer to seamless simulation. It doesn’t take much imagination to realize where a model of this ability may lead. Once advanced enough, there will be opportunities to run risky geoengineering simulations, like cloud seeding, or to calculate whether a certain endangered species is worth protecting.

Running these simulations in the cloud is a good step away from the historical norm, in which things like a nuclear reactor meltdown are tested in real life. But there is a risk of jumping from the simulation to reality. The neat lines of code and computerized data points don’t always translate into the messy natural world of atoms and physics.

Take, for example, the recent “resurrection” of direwolves, a canine species native to the Americas that went extinct some 10,000 years ago. It is the first experiment of a private biotechnology company on a mission to de-extinct species by splicing preserved DNA into those of a common ancestor alive today. But whether Romulus and Remus—the two puppies teething in some secret laboratory—are actually direwolves or just genetically modified gray wolves is debated. Is a species defined by a sequence of genomes, or is it also dependent upon its behavior in relation to the world in which it lived? De-extinction technology is one answer to today’s extinction crisis, but it raises a more profound question: what is the point of reviving a species without addressing the reason they went extinct in the first place?

To believe in the dire wolves' resurrection is to believe that complex systems can be conjured from simple symbols. It is a comforting thought: that if all else fails, we can preserve that which we cherish most with some code and a cloud, whether it be woolly mammoths, Tuvalu, or humanity itself.

Digital Seed Dispersal

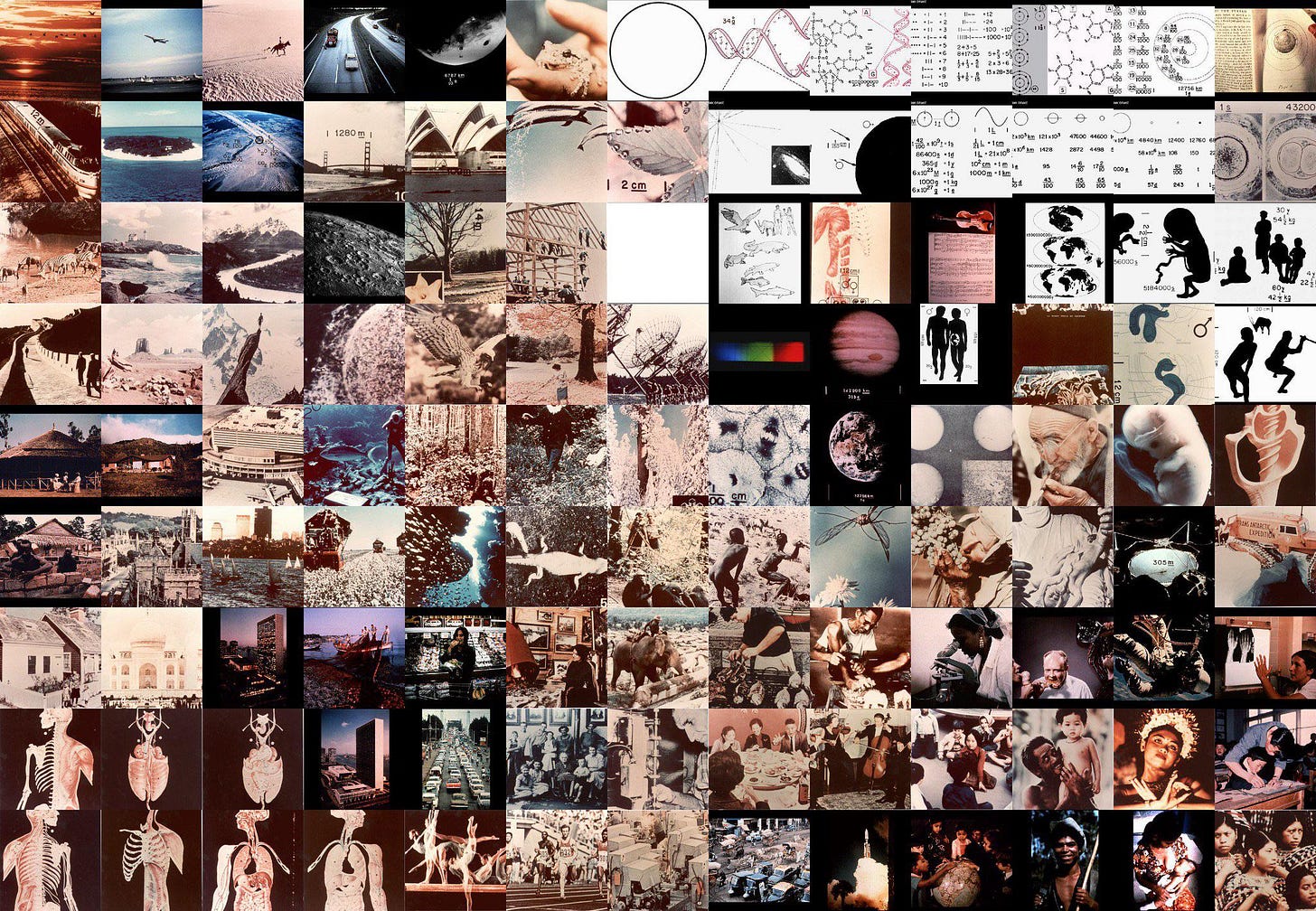

At the time of writing, Voyager-1 is 15,523,096,451 miles from the sun. It travelled another 42 miles in the time it took you to read that sentence, assuming you skimmed over the 11-digit figure (which you did). The satellite was hurtled into orbit in 1977 along with its (physical) twin, Voyager-2, and has been beelining through the cosmos ever since. It contains nothing short of humanity compressed.

Its famous passenger-payload, The Golden Record, represents a seed of Earth and a “warm Earthly greeting” for aliens. Etched into its gold-plated copper are the sounds of thunder, whales, birds, musical compositions, sentences in 55 languages, and 116 images that include the location of our solar system (which could prove to be a bad move), a fertilized ovum, and a man eating a constellation of grapes.

The statistical probability of aliens ever finding Voyager-1 is likely low, partly because space is big and partly because, despite the rather large number of planets, it appears so barren of life. The Fermi Paradox puts the statistical fact that there should be abundant intelligent life in the cosmos against the cold hard reality that we haven’t found any satisfying evidence of extraterrestrials yet.

There are a number of answers to the paradox, including one that suggests we live in a "dullsville suburb,” as the SETI Institute puts it. But another theory has a more sinister answer to this great silence. It proposes that aliens might just be living in virtual heaven, a computerized serenity of sorts. The end stage of all intelligent evolution might just be the development of a blissful simulation to escape bodily mortal coil. Voyager-1 would then pass by unnoticed as it beeps idly into the void.

But if life exists and they were to lift their alien faces from the proverbial sand or perhaps some viscous goo, see our little seed, and grab it, they would find an incomplete representation of Earth. Voyager-1 includes no images of war, suffering, or evil. It makes no mention of how deeply we’ve ravaged the planet.

The grand project of creating a virtual Earth may not save us—modeling climate scenarios and acting on their outcome are two very different challenges. If that’s the case then perhaps we’ll use the last of our resources to launch a Voyager-3 carrying a hard drive with Earth’s digital twin to sail through that black firmament in search of another hospitable planet. Perhaps this version will hold the memory of simulated floods and wildfires etched into its code, a warning of our folly and the message that some of us tried. Over that glitchy simulation a voice might say, “as our lands disappeared, we had no choice but to become the universe’s first digital species.”

Written and photographed (unless otherwise indicated) by Ryder Kimball

All of your pieces are beautiful, but this one was powerful enough to make me tear up while reading it. It’s utterly heart-breaking to think about how much investment is going into creating digital worlds at the expense of the real world.